|

THE YOOJUNG TIMESyoojungtimes.com |

Korean Development ModelAuthoritarian Industrialization and Struggle Democracy2004-05-23 |

Korean Development Model

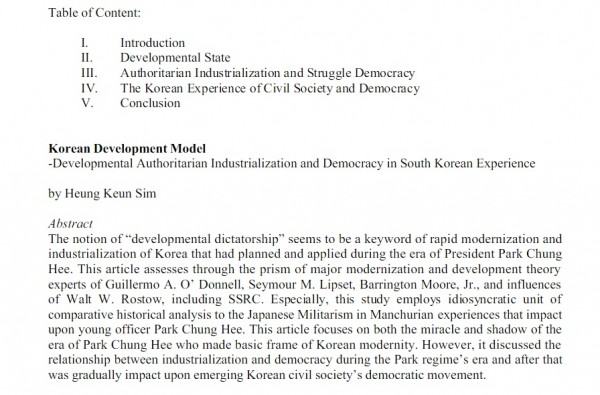

Table of Content:

I. Introduction

II. Developmental State

III. Authoritarian Industrialization and Struggle Democracy

IV. The Korean Experience of Civil Society and Democracy

V. Conclusion

Korean Development Model

-Developmental Authoritarian Industrialization and Democracy in South Korean Experience

by Heung Keun Sim

Abstract

The notion of “developmental dictatorship” seems to be a keyword of rapid modernization and industrialization of Korea that had planned and applied during the era of President Park Chung Hee. This article assesses through the prism of major modernization and development theory experts of Guillermo A. O’ Donnell, Seymour M. Lipset, Barrington Moore, Jr., and influences of Walt W. Rostow, including SSRC. Especially, this study employs idiosyncratic unit of comparative historical analysis to the Japanese Militarism in Manchurian experiences that impact upon young officer Park Chung Hee. This article focuses on both the miracle and shadow of the era of Park Chung Hee who made basic frame of Korean modernity. However, it discussed the relationship between industrialization and democracy during the Park regime’s era and after that was gradually impact upon emerging Korean civil society’s democratic movement.

I. Introduction:

How to related success of Korean industrialization and change of Korean political system? Ultimately speaking, why Park’s bureaucratic-authoritative notion was failed to implement sustained authoritarian institutionalization in Korea, although Park had been made successful national economic growth and transformed industrialization? How could evaluate the relationship between industrialization and democracy during the “take-off” developmental state in Korea?

By and large, it is generally assessed about the Korean political circumstances: The most important achievements of Korea during the late half of twenty century can be appreciated as, firstly, emancipated from brutal colonial Japanese rule in 1945 as the Allies’ winning result of WWII and establishment of the nation-state (although divided states- DPRK: North and ROK: South) which is the negotiated truce result after the Korean War in 1953; secondly, realizations of successful revolutionary transition of nation’s industrialization and democratization. For Korean, the industrialization meant achieving value; so, the impact upon industrialization is largely bigger than mere satisfactions of its material benefits. Through the successful industrialization, Korean can be able to speak and participate in international affairs, whereas, within the World system’s requirement of necessary formations with basic materialistic independent unite of nation-state-economy.

Even if the successful establishment of nation-state-economy of Korea has very important historical meaning, such questions on “how to success” or “what kind of path to following for success” are equally important for the analysis of Korean political economy. Seeing through the comparative prism, although the weight of Koreans’ paid costs and pains were relatively less, but it should not be neglecting for justify as saying as ‘nothing- but- only authoritative dictatorial rule’ would have essential during the stage and trying to rationalize its shadow of darkness under the developmental dictatorship of Park, Jung Hee. In other words, though the developmental industrialization had successes, dictator regime of Park used it as a useful tool for controlling his political regime’s survival and deepening on the dichotomy of Cold War tensions, such as easily able to use “ideological interpellation” as like Louis Althusser’s concept; also, it is as much his strategic regime holding on polarized bandwagon of the anti-communism, such as joining and sending the Koran Marin and Army troops into the U.S. leading ‘dirty’ Vietnam War. Moreover, this industrial development of Park regime created asymmetrically centralized political and bureaucratic institutions and also made privileged conservative “gae-bol” (Korean styled rich-conglomerates-enterprises: the government has strategically selected certain business category and its business leaders for sustaining conservative political economic alliances) class for deepening of alignment of conservative political and economic power. However, such polarized notion of authoritative industrial dictatorship remains some of negative legacies in Korean political and social areas.

The notion of “developmental dictatorship” is a keyword of rapid modernization and industrialization of Korea that had planned and applied during the era of President Park Chung Hee. This article assesses both the miracle and darkness of the era of Park Chung Hee who made basic frame of Korean modernity. However, it would be a valuable discussion that the relationship between elites’ applying rapid authoritarian industrialization notion and struggle for democracy during the Park regime’s era and the after that was resulted gradually emerging Korean civil society’s democratic movement from below.

II. Developmental State:

Through some of important comparative development study’s literature review, it can able to begin with discussing about the highlighted issue on ‘political effect by the industrialization’; there can be academic searching directions are possible to explications to Korean cases. 1. Guillermo A. O’Donnell (1973) “Modernization and bureaucratic-authoritarianism”; 2. Seymour M. Lipset (1960) “Political Man”; 3. A. Przeworski (1997); “Modernization Theories and Facts”; 4. Barrington Moore, Jr. (1966) “Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy.” However, it is unnecessary to remarks in Korean development study case that it is to be deserved giving excellent epistemic credits belong with a significant contribution of W.W. Rostow’s major development theory as framed as “take-off” in “The Stages of Economic Growth” in which to be reflected as a fine pragmatic theory application with actual reality, at least, poor and underdeveloped era in 60s’ Korean case. For Korean elites’ the option was to be limited and only independent variable option was catching up the stage of “take-off”.

First of all, G. O’ Donnell theory’s main starting point is the change in political system is directly related as if a byproduct of a state’s propelled stages during industrialization process. O’ Donnell depicted Latin America countries’ experiences of industrialization that 1) when an economic system run with the primary industry, such as, exporting “staple” economy of agricultural products and coal and mining, there had positioned politically managed by the ‘oligarch’ system. And 2) when the transitional era of 1930-1950 as implementing the ISI (import substitute industry) oriented economic stage had reviled and preferred on the ‘Populism’ centric governing; such as, the Vargas regime of Brazil in 1950-54, or Argentina’s Peron regime in 1946-1955. And 3) when such an industrial change in transition that into “export-oriented” manufactured economic system had signified and attached into the BA model (system of bureaucratic-authoritarianism), and it resulted as more deepened system change with the previous stage of ISI; such as, the early 80s’ Brazil and Argentina, after 1973 of Chile and Uruguay, or the situations of current Mexico after the year of 1985. (Lee, Jung Bock: 2006).

Those above exampled cases show that under the “oligarch” system, there were very limited political competitions existed among the challengers. And the “populist” system had been existed a wide scope of political competitions in which included its notion of “political activation” were allowed with the people’s participation, while the BA system had willing to close the range of people’s participation and so the public and civil sectors had politically and economically excluded by the technocrat’s absolute ruling centric positions. O’ Donnell opinioned that during the early ISI stage there had existed much of freedom of establishment of “populist system” through an opened the political activation and the state’s governing institutions could be able to accept the people’s economic demands only in the early stage. In contrast, the late stage of ISI or the post ISI stage had faced direct dilemma that no longer accept people’s demands and hope; moreover, the governing elites see that the establishment of the strong BA system would be only solution for deepening industrialization and providing enough developmental cash finances from the FDI (foreign direct investment), through effectively excluding people’s demands. Consequently, O’ Donnell sees that the establishment of BA system can be possible through the action of coup and alliances of the capitalist, technocrats, and military officers. However, O’ Donnell ultimately pointed that the most important and decisive independent variable to the establishment of BA system is the “developmental stage of industrialization” itself, rather than a possible variable of the military. (G. O’ Donnell: 1979)

In the light of O’ Donnell, the forming of first opinion is possible regarding to the analysis of Korean industrialization which study category can be applied O’ Donnell’s Latin America experiences of the relationships of industrialization with the political system change.

In the application of the O’ Donnell’s opinion to the Korean case, the Korea’s third republic era from 1963 to 1972 positioned as ISI stage, and it had been signified a populism centric element and governing pathos of revolutionary regime of Park, Chung Hee. And right after the 1972, it had been “deepening industrialization”, therefore, the Korean political system had been forced to galvanize into the authoritative-bureaucratic system and transition from a pseudo-democratic system to the strong “Yu-sin” system (Korean version of the BA system). (Kang, Min: 1983).

The era of 70s of Korea, the logical area of development, there claimed it was imperatively needed to be implement more “deepening industrialization” progress, and so much required catch-up financial flow of foreign investments. By the result, the added logic of Korean development can be claimed and justified it had to inclined and forced into the BA system against the populist pathos.

In contrast, another significant opinion about the impact upon Korean industrialization can be explicated by the revisionist literature of Professor Choi, Jang Jip, which is the rejection of the O’ Donnell’s study opinion and premise that the economic and industrial stage of “causality” has directly affected to the change in political system. (Lee, Jung Bock: 2006). According to Professor Choi, the O’ Donnell’s setting premise of the cause and effect is not exactly relevant to the Korean industrial developmental case. First of all, the young military officer Park’s military revolutionary coup in May 16, 1961 occurred nothing by the social and economic “pull factor” but only by the “push factor” of a hyper growth of Korean military bureaucratic system. Moreover, the political system change into the “Yu-sin” system in 1972, as a strong BA system is also directly caused for building the Park regime’s idiosyncratic ambitions of constant survival through the centralized total executive nexus of major governing institutional power of regulation, controlling, information, and especially setting up the National Security agency for logical manipulation of “ideological interpellation”, instead of social and economic tension. In other words, the era of “Yu-sin” in the early 70s’ Korea had not been existed as much as the causal situations of social and economic Latin American experiences of the O’ Donnell’s BA theory.

Second most important relevant analytic theory about the Korean industrialization study is subject to the “modernization” theory; such as, Seymour M. Lipset (Political Man), and A. Przeworski (Modernization). According to Lipset, simply saying, the successful transformation of democracy is directly interconnected with the economic growth and industrialization. Economic growth can affect to affluence spreading of the middle class status, and also influence higher educations for implement the value of democracy and can enjoy civilized cultural attitude for accept the value of democracy through participations. Therefore, only the economic growth and modernization can make politically institutionalized entity which is legitimately mobilized and revealed various social conflicts and reattached the social cleavages by the mechanism of dialectics of “conflict” with “unity”.

However, some scholar criticized that this Lipset’s premise can not easily applied into the case of Korean economic development or Latin America experiences because of Lipset’s theory has much depended and reflected the Western and European economic growth and development experiences.

Third and last, Barrington Moore, Jr. states that the issue of the consequences of political system is largely interrelated, interconnected with the pattern of early stage of modernization; whither ways resulted to the democracy, or the fascist dictatorships, or the communist revolution is the matter of “early stage” of modernization. (Barrington Moore, Jr.: 1966) Briefly speaking, Barrington Moore sees the origin of modern democratization is modified and leaded by the commercial oriented classes of bourgeois. The Korea’s bourgeois class, so-called “geabol” is created and constantly prospered through the careful selections among industries by the authoritative developmental elites’ hands, as directing on indication planning for each 5 years’ termed development scheduling for meet target goals; where those works are become a legacy of the Korean “developmental state” leading bureaucratic-authoritative regimes of Park, Jung Hee, Jun Doo Hwan, including Rho, Tae Woo. However, most importantly, the Korean case is contrasted with the Barrington Moore’s, because the students and white-colors’ massive mobilized nation-wide scaled movement for achieving democracy made an “exit path” as a transitional door from the BA system to democratic system. (Choi, Jang Jip: 2002)

To discuss this issue, it needs to, in advance, look at the key term of “developmental-state” instead of focused on Japan itself. The main reason for employing the ‘developmental-state’ model is the model was applied by the developmental dictator President Park, Jung Hee and his regime’s intensive administrations to implementations as major developmental policy since the coup year in 1961 to the 1979 his assassination year, and the developmental-state policy was extended until 1987 as the year of complete transition to the democracy, as his successor Presidents Jun, Doo Hwan and Rho Tae Woo, who were risen from military elite statues.

By and large, the ‘developmental state’ concept can be reflected through the Chalmers, Johnson’s study of Japan’s economic development. Johnson finds out successful industrial transition of Japan case can be explicated as the centralized government elites’ leading role with development and pretty much free from the sub-social pressures or civil society. Therefore, Japan’s elite leading role during the developmental stage is much similar with Korean case. Which means that, according to C. Johnson, free of elite conflict can be realized to successful transition of economic development that is much different with classical M. Weber’s bureaucratic system theory or the liberal market oriented developmental theory of Lipset’s.

Similarly, M. Woo-Cumings also sees and holds C. Johnson’s study that Japan and Korean case is overlapped with the logic of ‘developmental-state’ model which can be explained and justified as a rationally planned state centric market interferes for economic growth. (Meredith Woo-Cumings: 1999 and Bruce Cumings: 1997) and also can see (Alice Amsden: 1989 “Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization”) Prof. Cumings says “Economic Planning was another wrinkle that Park borrowed either from the Japanese in Manchuria in the 1930s or from the North Koreans thereafter; successive five-year plans unfolded from the hallowed halls of Economic Planning Board (EPB), known as Korea’s MITI, after Japan’s Ministry of Trade and Industry. The First Five-Year Plan was to run from 1963 through 1967, but Americans in the Agency for International Development (AID) mission did not like it, and refused to certify it for foreign lending. It never really got off the ground. The Second Five-Year Plan (1967-71) was more to their liking, but the Koreans had also learned how to muddle American minds.” (Bruce Cumings: 1997. pp. 313-314.)

Comparative application of the President Park’s developmental model case to the Japan’s experience is some what controversial and there are lots of on-going debates in the field of academia because of there exists various study facts of similarities and differences. Firstly, the similar case can be analyzed by focusing on the ‘timing’ in the development. For example, Albert O. Hirschman defined its ‘industrial timing,’ in which the one category is the ‘Late-industrialization’ and the other is the “Late-late industrialization”. According to A. Gerschenkron, Late-industrialization is indicated to the cases of Germany, Italia, Russia, and Japan that are one stage behind to the early industrialized case of developed England. And the ‘late-late industrialization’ is termed to point out the developing Third world, such as Latin American countries.

Clearly, Korea case is categorized into the nominal definition of “late-late industrialization” as much similar with developing Latin America countries when it reflected by the analysis of A. Hirschman’s. Interestingly, it can be argued that actually the Korean case of industrialization is rather much more familiar and close to the category of “late-industrialization” than the late-late industrialization; when one sees the Korean case’s unique preceding mode and its synthesized characteristics of the domestic political system with industrialization.

Consequently, President Park, Chung Hee’s military supported bureaucratic-authorities development mode and procedure is much more similar to Japan’s authoritative regime in 1930s than the experiences of Latin American military regimes. (Choi, Jang Jip: 2002) In addition that looking into the prism of the individual analysis, Korean industrialization was largely directed by an idiosyncratic President Park’s personal ruling idea and his vision on the national political economics. In quotations of Bruce Cumings, it is noted as, “In Park’s first book after the coup, Our Nation’s Path, regime scribes lauded the Meiji Restoration as a great nation-building effort; but it was really the ‘Manchurian model’ of military-backed forced-pace industrialization that Park had in mind.” (B. Cumings: 1997. p. 311.)

Chalmers Johnson also rightly called attention to the Manchurian model of military-backed foced-pace to that “Manchukuo-group” in his seminal MITI and the Japanese Miracle (1982). “Park Chung Hee was a stolid son of Korea’s agrarian soil who, like Kim Il Sung, had come of age in Manchuria in the midst of depression, war, and mind-spinning change. In this radicalized milieu he had witnessed a group of young military officers organize politics, and a group of young Japanese technocrats quickly build many industries-including Kishi Nobusuke, who later became prime minister of Japan.” (Chalmers Johnson: 1982)

However, the study of Korean model, so far, has been analyzed various ways and overproduced its volumes from international and domestic academia by comparative study method; such as, comparative political development study of Korea and Taiwan model v. Syria and Turkey model cases by the U. of Virginia Professor David Waldner’s thesis of “State Building and Late Development”. Professor Waldner employed the “levels of elite conflict” as an basic “unite of independent variable” for the analysis: While Syria and Turkey had high levels of elite conflict existed, relatively Korea and Taiwan had experienced “low levels of elite conflict” that can smoothly transited to the stage of “Developmental-state” in which stage therefore can get enhanced capacity to create “value” and “sustainable development” based on production of low-cost goods that are competitive on world markets with continuous shifts into higher value-added goods. (David Waldner: 1999)

III. Authoritarian Industrialization and Struggle Democracy

In looking back especially the history of modern Korean democracy, the relationship between authoritarian industrialization and democracy was easily seen its critical nature not only Korean themselves but also all foreigners of good-hearted epistemic community can get empathic feeling as disturbing contrast during the Park’s regime. In Korean industrialization case, there are significant contrasting opinions are still remained that regarding “how to interpret” the relationship between industrialization and democracy. The first opinion remarks that though economic growth had been speeded during the Park’s regime, there was lack of genuine sense of democratic political values, including political spaces in democracy. The other states that political democracy was largely sacrificed in order to promote economic growth first to the national policy as inevitability was necessary during the era of Cold War international system. So, the latter point of view again can be deduced into sub-opinionated position that the high level of economic growth output during the Park’s regime can be appreciated as an indomitable developmental leadership and prudent as its well-planned policy machine administrations of the Park regime that preferred cohesive nexus building in capitalism and thus excluding people and labors were allowed oppression in the logic of high level of economic growth first development policy. (Ho Cheol Son 1995: pp. 147-148)

However, two contrasting viewpoints reflect that the driving force of economic growth under the Park’s leadership was composed of three dimensional administrative factors of internal and external context, and ideological conflictions with systemic adjusting reflection on competitive international environment of world capitalism, land reform, the historical and geopolitical conditions of the division in Korean peninsula, at the same time, the strong role of the state and an abundant and diligent labor forces in low wages. The central issue that surrounding the relationship between economic growth and democracy can be reflected by the counter-factual assumption possible; such as, if it were progressed under a genuine democratic political system, then there were situation as hard to promote rapid economic growth. In other words, the question is that it can be justified as an authoritarian political regime is an inevitable and necessary factor for achieve economic growth in the actual processing stage of “take-off” of development. Seeing form the level of fact judgment, which regarding to this issue’s historical modernization experiences looked to be pessimistic. For instance, there were empirical patterns existed in reality where a developing state that faced overcoming efforts against international capital markets’ pressures into the periphery, and at the same time there were assigned for the achieving “take-off” stages to the late industrialization, moreover there were also temptations of inevitable setting up highly centralized state apparatus requirement as sacrificing short term interests through avoiding pressures of redistributions from multitude. Where there are examples of the former Soviet Union and China’s state socialist development, and represented as late capitalist development actors of Japan and Germany are no exceptions to this developmental rule as provided historical evidences (Ho-Ki Kim, 1995). In other words, the extensive regime of accumulation founded on low-wage controlling, and long-hour labor orientations seem to be closed to a “selective affinity” with a coercive and violent and oppressive kind of bourgeoisie state rather than a care and deal with “class-friendly” oriented state. (Ho-Ki Kim, 1995)

Another counter-factual debating study question is possible when it consider under factual and normative tension that the relationship between economic growth and democracy, there is the argument and question in contradiction that whether authoritarianism looked to be more efficient in stimulation economic growth than democracy, so it may be justified that developing state ought to be pursued under the guiding in authoritarianism and therefore democracy could be restrained its degree and durations. Can it be justified; whether economic growth and its capital order and its astute management of stability in a system of capital protocol under the logic of dependency which would be more important than categorical Kantian systemic imperatives ethics of human rights, political freedom and equality of civilian rights? For considering this issue, Professor Ho-Ki Kim suggests that it is reasonable to review past social survey of certain class level as an inferring on the evaluation of history because of it is affected by pervasive of the attitudes at the time which it is interpreted. In 1967, the social survey focused at the level of intellectuals presented interesting results although it was not enough number of survey participants. (Hong Seung-jik, 1967: pp. 161-167. this survey was administered to 761 university professors and 754 news press reporters) The questionnaire was “What would you think is the most important factor or element of modernization when considering the currently given state of affairs in South Korea?”, an large proportional response outcomes as an overwhelming 29.6% of respondents stated “industrialization” and 22.6% stated “improvement of citizens standard of living”, while only 7.1% of respondents stated “the democratization of the political system” and “13.0% stated “the promotion of rationalism and science in daily life”. Interestingly, moreover, the result in which 60% of respondents replied that they would sacrifice personal freedom for the sake of economic development presents almost average intellectuals attitude toward strong hope to modernization support during the underdeveloped era at sixty in South Korea.

As the Korean intellectual’s survey shows that during the 1960s the major issue of industrialization carried an overwhelming importance in popular attitudes. Horrible and devastating memories of the Korean War reflected on strong desire and hope for setting up reestablishing order and stability through persuasions on improving living conditions as overcoming very plight reality of lack of “basic subsistence strategy” as under-nutrition food quality, that related the break agricultural farming circumstances since immediately after the Korean War. Therefore such hopes and basic subsistent material desires naturally provided the mental psychology for support industrialization success although it is planned by demanded authoritarian top-down styled national scaled mobilization. Yet, considering other side of ethical sense about it, it seems to very uneasy to pardon and accept its justification such ruling that largely executed and administered authoritarianism of the Park regime while sacrificing ethos of democracy and regarding on only can appreciate because economic growth was achieved rapidly. Although there had been happened that selective affinity between political authoritarianism and early stage of pre-capitalist industrialization and large number of multitudes desired economic growth, the one-sided and unbalanced justification for authoritarian regimes hard to be given some of positive appreciation.

However, the choice between economic growth and democracy is largely oversimplified various human values and it was many parts regarding on an interpretation of biased historical side that only focused on results without sufficient consideration of its causality and origin by using righteous logos and its processes in ethos. Ultimately, the important considering aspect is how much effort had been done by the Park regime’s investment in combining at the degree of proportional equality of economic efficiency and democratic freedom criteria. For instance, the series of disturbing political reforms such as the regime’s artificial alterations of the Constitution through astute amendment for building permanent political power nexus which enabled Park to run for a third term in violating of Presidential nomination rule and setting up October “Yushin” system which contradicted procedural democracy and the uncomfortable authoritarianism that evidenced the extent of the undemocratic and exclusionary nature of the Park regime.

Such a complex issue needs to be look at forest as if seeing overall big picture rather than some trees. Although the evaluations of industrialization and democracy to be considered empirical problematic area that related experiential problems, yet, it is also innate a theoretical comparative point of dispute. For instance, there is problematic theoretical hypothesis of modernization; according to Lipset, if an economy is developed in certain positive GNP output, then the possibility for the realization of democracy is escalated (Lipset, 1980). Viewing from scaled perspective position, there can see a significant correlation between economic growth and democracy, yet there also exists various contexts and contingency can be found existence of intermediate variables between two relations. For instance, according to Rueschemeyer and Stephens, as capitalist industrialization gradually increasing the scope of density in civil society in which augment of civil society can set up the foundation for political systematization of the governed classes of society, it can also able to transforms the working class into a checking and balancing power as impact upon the authority of the state. (Rueschemeyer, Stephens and Stephens, 1992: They defined civil society as a totality of social institutions and associations, both formal and informal that are not strictly “production-related” nor “governmental” or familiar in character) In such historical analysis through experiences, in the relationship between economic growth and democracy, the major conditions of the growth of civil society and the formation of the working class are important in their roles as can be dealing intermediate variables to the progress and its feedback with their surrounding environments.

IV. The Korean Experience of Civil Society and Democracy

Despite normally there is having a sustainable long term tendency as quoted “viable” democracy in the usage of G. Almond, however, there exists relativity that when democratic path would situated in the short term, there to be faced some possibility for a retrogression within democracy depending on the state’s surrounding conditions. The causality is the direction of democratization is determined by the logic and process of balance of power between power bloc political forces and non-power bloc political forces when the existing governing system is confronted by crisis. Under the Park regime, despite the continuing social movements by non-power bloc political forces such as civil society and the working class, they were not mature enough to rival the power bloc political forces. However, the Korean bourgeoisie did not much embrace democracy and were perceived rather be the most faithful allies to the authoritarian regime (Shin Gwang-yeong, 1995: p. 115). The theory assertion by Barrington Moore Jr. that “without the bourgeoisie, there is no democracy” is not exactly relevant in the case of South Korea. At the same time, the assumption of modernization theory that economic growth contributes to the development of democracy would be reasonably appropriate when only if the growth of civil society were progressed widely and active participations of the working class were conditioned as if an important acting unit of intermediate variables (Jeong Sang-ho, 1966). True, it is a fact that, the potential seeds of viable democracy were cultivated in the internal dynamics of the industrialization promoted by the Park regime during the 1960s and 1970s (Ho-Ki Kim, 1995). Before it could actually sprout through the June Democratization Movement in 1987, such desire for civil society participation democracy had to face harsh suffering by the government of another oppressive authoritarian regime under Chun Doo-hwan who is an almost exact little figurative mimesis of Park, Jung Hee.

V. Conclusion:

Since the era of 1960s to 1980s, the Korean industrialization process is very rapid, and it marked unprecedented world’s historic economy growth record as its annually constant increasing of the volumes of growth. Such rapid developmental state leading industrialization process can affect the political system’s transition. In the year of1972, that political transition was actually happened that change was from a pseudo-democracy system to a polarized authoritative dictatorship system. This study finds that such political system change occurrence is not much actually related with the claims of necessity of ‘deepening’ industrialization. On the contrary, that transition was largely interrelated with the real causalities: the internal causalities are the large governing entity size, and its constant growth of military backed bureaucratic institutions, and especially President Park’s idiosyncratic ambitions on permanently holding Presidential power as his attachment on the dictatorship oriented power nexus web system; an external causality was largely related with the change of the U.S. foreign policy direction to Asia that normalization with China and dialogues with communist regimes during the Nixon era also affected to Park’s leadership. And President Park sees the Nixon doctrine as a wonderful chance to building his own individual political power nexus line and a great chance to free from the United States’ constant support and influences on the value of democratization. In fact, the Nixon doctrine had executed significantly sudden reducing Korea’s developmental finance budget and quantitative material defense security support. Thus, the year of 1972, the Korean political system change that turn reinforcement into the strong bureaucratic-military-authoritative Korean “Yu-sin” system was occurred autonomously within the area of 1) internally already given domestic conditions of the largely expending size of Korean political and military defense institutions in the era, and 2) external circumstance of World affair that the Nixon’ doctrine’s change in foreign policy impact upon North-East Asia, instead of the necessity and awareness of ‘deepening’ economic development.

Bibliography

Adam Przeworski and Ferdinando Limongi. “Modernization: Theories and Facts.” World Politics Vol. 49, No. 2. 1997.

Albert O. Hirschman. “The Political Economy of Import-Substituting Industrialization in Latin America.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 82, No. 1. 1968.

Alice Amsden. “Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization.” New York: Oxford University Press. 1989.

Bruce Cumings. “Korea’s Place in the Sun.” A Modern History. W.W. Norton & Company New York, NY: London. 1997.

Chalmers Johnson. “MITI and the Japanese Miracle.” Stanford: Stanford University Press. 1982.

Choi, Jang Jip. “Democracy after the Democratization.” Humanitas Press. Seoul Korea. 2002. (in Korean)

Lipset, Seymour M. “Political Man.”: The Social Bases of Politics. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.1980.

Meredith Woo-Cumings. “The Develpmental State.” Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1999.

Kang Min and Han, Sang Jin. “Bureaucratic-Authoritarianism in Korea.” Seoul National University Conference on the Dependency Issue in Korean Development. 1983.

Moore, Barrington Jr., “Social Origins of Dictatirship and Democracy.”: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston: Beacon Press. 1966.

O’ Donnell, Guillermo. “Modernization and bureaucratic authoritarianism.” Berkeley: University of California Press. 1973.

Hong, Seung-jik, Intellectuals and Modernization. (1967), Social Researdch Institute of Korea University. (in Korean)

Kim, Ho-Ki. “Modern Capitalism and Korean Society.” Seoul: Sahoebipeyngsa. 1995. (in Korean)

Lee, Jung Bock. “Analyzing & Understanding Korean Politics.” Seoul National University Press. 2006. (in Korean)

Ruschemeyer, Dietrich, Evelyne Stephns and J. Stephens, “Capitalist Development and Democracy.” Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1992.

Shin, Gwang-yeong. “The Concept and Formation of Civil Society.” in Pal-mu Yu and Ho-ki Kim (eds.), Civil Society and Civil Movements Seoul: Hanul. 1995. (in Korean)

Son, Ho-cheol, “50 Years of Korean Politics after Liberation.” Seoul: Saegil. 1995. (in Korean)

Waldner, David. “State building and late development.” Cornell University Press. 1999.

Web:

https://www.scribd.com/document/40604177/Korean-Development-Model-by-Heung-K-Sim

Table of Content:

I. Introduction

II. Developmental State

III. Authoritarian Industrialization and Struggle Democracy

IV. The Korean Experience of Civil Society and Democracy

V. Conclusion

Korean Development Model

-Developmental Authoritarian Industrialization and Democracy in South Korean Experience

by Heung Keun Sim

Abstract

The notion of “developmental dictatorship” seems to be a keyword of rapid modernization and industrialization of Korea that had planned and applied during the era of President Park Chung Hee. This article assesses through the prism of major modernization and development theory experts of Guillermo A. O’ Donnell, Seymour M. Lipset, Barrington Moore, Jr., and influences of Walt W. Rostow, including SSRC. Especially, this study employs idiosyncratic unit of comparative historical analysis to the Japanese Militarism in Manchurian experiences that impact upon young officer Park Chung Hee. This article focuses on both the miracle and shadow of the era of Park Chung Hee who made basic frame of Korean modernity. However, it discussed the relationship between industrialization and democracy during the Park regime’s era and after that was gradually impact upon emerging Korean civil society’s democratic movement.

I. Introduction:

How to related success of Korean industrialization and change of Korean political system? Ultimately speaking, why Park’s bureaucratic-authoritative notion was failed to implement sustained authoritarian institutionalization in Korea, although Park had been made successful national economic growth and transformed industrialization? How could evaluate the relationship between industrialization and democracy during the “take-off” developmental state in Korea?

By and large, it is generally assessed about the Korean political circumstances: The most important achievements of Korea during the late half of twenty century can be appreciated as, firstly, emancipated from brutal colonial Japanese rule in 1945 as the Allies’ winning result of WWII and establishment of the nation-state (although divided states- DPRK: North and ROK: South) which is the negotiated truce result after the Korean War in 1953; secondly, realizations of successful revolutionary transition of nation’s industrialization and democratization. For Korean, the industrialization meant achieving value; so, the impact upon industrialization is largely bigger than mere satisfactions of its material benefits. Through the successful industrialization, Korean can be able to speak and participate in international affairs, whereas, within the World system’s requirement of necessary formations with basic materialistic independent unite of nation-state-economy.

Even if the successful establishment of nation-state-economy of Korea has very important historical meaning, such questions on “how to success” or “what kind of path to following for success” are equally important for the analysis of Korean political economy. Seeing through the comparative prism, although the weight of Koreans’ paid costs and pains were relatively less, but it should not be neglecting for justify as saying as ‘nothing- but- only authoritative dictatorial rule’ would have essential during the stage and trying to rationalize its shadow of darkness under the developmental dictatorship of Park, Jung Hee. In other words, though the developmental industrialization had successes, dictator regime of Park used it as a useful tool for controlling his political regime’s survival and deepening on the dichotomy of Cold War tensions, such as easily able to use “ideological interpellation” as like Louis Althusser’s concept; also, it is as much his strategic regime holding on polarized bandwagon of the anti-communism, such as joining and sending the Koran Marin and Army troops into the U.S. leading ‘dirty’ Vietnam War. Moreover, this industrial development of Park regime created asymmetrically centralized political and bureaucratic institutions and also made privileged conservative “gae-bol” (Korean styled rich-conglomerates-enterprises: the government has strategically selected certain business category and its business leaders for sustaining conservative political economic alliances) class for deepening of alignment of conservative political and economic power. However, such polarized notion of authoritative industrial dictatorship remains some of negative legacies in Korean political and social areas.

The notion of “developmental dictatorship” is a keyword of rapid modernization and industrialization of Korea that had planned and applied during the era of President Park Chung Hee. This article assesses both the miracle and darkness of the era of Park Chung Hee who made basic frame of Korean modernity. However, it would be a valuable discussion that the relationship between elites’ applying rapid authoritarian industrialization notion and struggle for democracy during the Park regime’s era and the after that was resulted gradually emerging Korean civil society’s democratic movement from below.

II. Developmental State:

Through some of important comparative development study’s literature review, it can able to begin with discussing about the highlighted issue on ‘political effect by the industrialization’; there can be academic searching directions are possible to explications to Korean cases. 1. Guillermo A. O’Donnell (1973) “Modernization and bureaucratic-authoritarianism”; 2. Seymour M. Lipset (1960) “Political Man”; 3. A. Przeworski (1997); “Modernization Theories and Facts”; 4. Barrington Moore, Jr. (1966) “Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy.” However, it is unnecessary to remarks in Korean development study case that it is to be deserved giving excellent epistemic credits belong with a significant contribution of W.W. Rostow’s major development theory as framed as “take-off” in “The Stages of Economic Growth” in which to be reflected as a fine pragmatic theory application with actual reality, at least, poor and underdeveloped era in 60s’ Korean case. For Korean elites’ the option was to be limited and only independent variable option was catching up the stage of “take-off”.

First of all, G. O’ Donnell theory’s main starting point is the change in political system is directly related as if a byproduct of a state’s propelled stages during industrialization process. O’ Donnell depicted Latin America countries’ experiences of industrialization that 1) when an economic system run with the primary industry, such as, exporting “staple” economy of agricultural products and coal and mining, there had positioned politically managed by the ‘oligarch’ system. And 2) when the transitional era of 1930-1950 as implementing the ISI (import substitute industry) oriented economic stage had reviled and preferred on the ‘Populism’ centric governing; such as, the Vargas regime of Brazil in 1950-54, or Argentina’s Peron regime in 1946-1955. And 3) when such an industrial change in transition that into “export-oriented” manufactured economic system had signified and attached into the BA model (system of bureaucratic-authoritarianism), and it resulted as more deepened system change with the previous stage of ISI; such as, the early 80s’ Brazil and Argentina, after 1973 of Chile and Uruguay, or the situations of current Mexico after the year of 1985. (Lee, Jung Bock: 2006).

Those above exampled cases show that under the “oligarch” system, there were very limited political competitions existed among the challengers. And the “populist” system had been existed a wide scope of political competitions in which included its notion of “political activation” were allowed with the people’s participation, while the BA system had willing to close the range of people’s participation and so the public and civil sectors had politically and economically excluded by the technocrat’s absolute ruling centric positions. O’ Donnell opinioned that during the early ISI stage there had existed much of freedom of establishment of “populist system” through an opened the political activation and the state’s governing institutions could be able to accept the people’s economic demands only in the early stage. In contrast, the late stage of ISI or the post ISI stage had faced direct dilemma that no longer accept people’s demands and hope; moreover, the governing elites see that the establishment of the strong BA system would be only solution for deepening industrialization and providing enough developmental cash finances from the FDI (foreign direct investment), through effectively excluding people’s demands. Consequently, O’ Donnell sees that the establishment of BA system can be possible through the action of coup and alliances of the capitalist, technocrats, and military officers. However, O’ Donnell ultimately pointed that the most important and decisive independent variable to the establishment of BA system is the “developmental stage of industrialization” itself, rather than a possible variable of the military. (G. O’ Donnell: 1979)

In the light of O’ Donnell, the forming of first opinion is possible regarding to the analysis of Korean industrialization which study category can be applied O’ Donnell’s Latin America experiences of the relationships of industrialization with the political system change.

In the application of the O’ Donnell’s opinion to the Korean case, the Korea’s third republic era from 1963 to 1972 positioned as ISI stage, and it had been signified a populism centric element and governing pathos of revolutionary regime of Park, Chung Hee. And right after the 1972, it had been “deepening industrialization”, therefore, the Korean political system had been forced to galvanize into the authoritative-bureaucratic system and transition from a pseudo-democratic system to the strong “Yu-sin” system (Korean version of the BA system). (Kang, Min: 1983).

The era of 70s of Korea, the logical area of development, there claimed it was imperatively needed to be implement more “deepening industrialization” progress, and so much required catch-up financial flow of foreign investments. By the result, the added logic of Korean development can be claimed and justified it had to inclined and forced into the BA system against the populist pathos.

In contrast, another significant opinion about the impact upon Korean industrialization can be explicated by the revisionist literature of Professor Choi, Jang Jip, which is the rejection of the O’ Donnell’s study opinion and premise that the economic and industrial stage of “causality” has directly affected to the change in political system. (Lee, Jung Bock: 2006). According to Professor Choi, the O’ Donnell’s setting premise of the cause and effect is not exactly relevant to the Korean industrial developmental case. First of all, the young military officer Park’s military revolutionary coup in May 16, 1961 occurred nothing by the social and economic “pull factor” but only by the “push factor” of a hyper growth of Korean military bureaucratic system. Moreover, the political system change into the “Yu-sin” system in 1972, as a strong BA system is also directly caused for building the Park regime’s idiosyncratic ambitions of constant survival through the centralized total executive nexus of major governing institutional power of regulation, controlling, information, and especially setting up the National Security agency for logical manipulation of “ideological interpellation”, instead of social and economic tension. In other words, the era of “Yu-sin” in the early 70s’ Korea had not been existed as much as the causal situations of social and economic Latin American experiences of the O’ Donnell’s BA theory.

Second most important relevant analytic theory about the Korean industrialization study is subject to the “modernization” theory; such as, Seymour M. Lipset (Political Man), and A. Przeworski (Modernization). According to Lipset, simply saying, the successful transformation of democracy is directly interconnected with the economic growth and industrialization. Economic growth can affect to affluence spreading of the middle class status, and also influence higher educations for implement the value of democracy and can enjoy civilized cultural attitude for accept the value of democracy through participations. Therefore, only the economic growth and modernization can make politically institutionalized entity which is legitimately mobilized and revealed various social conflicts and reattached the social cleavages by the mechanism of dialectics of “conflict” with “unity”.

However, some scholar criticized that this Lipset’s premise can not easily applied into the case of Korean economic development or Latin America experiences because of Lipset’s theory has much depended and reflected the Western and European economic growth and development experiences.

Third and last, Barrington Moore, Jr. states that the issue of the consequences of political system is largely interrelated, interconnected with the pattern of early stage of modernization; whither ways resulted to the democracy, or the fascist dictatorships, or the communist revolution is the matter of “early stage” of modernization. (Barrington Moore, Jr.: 1966) Briefly speaking, Barrington Moore sees the origin of modern democratization is modified and leaded by the commercial oriented classes of bourgeois. The Korea’s bourgeois class, so-called “geabol” is created and constantly prospered through the careful selections among industries by the authoritative developmental elites’ hands, as directing on indication planning for each 5 years’ termed development scheduling for meet target goals; where those works are become a legacy of the Korean “developmental state” leading bureaucratic-authoritative regimes of Park, Jung Hee, Jun Doo Hwan, including Rho, Tae Woo. However, most importantly, the Korean case is contrasted with the Barrington Moore’s, because the students and white-colors’ massive mobilized nation-wide scaled movement for achieving democracy made an “exit path” as a transitional door from the BA system to democratic system. (Choi, Jang Jip: 2002)

To discuss this issue, it needs to, in advance, look at the key term of “developmental-state” instead of focused on Japan itself. The main reason for employing the ‘developmental-state’ model is the model was applied by the developmental dictator President Park, Jung Hee and his regime’s intensive administrations to implementations as major developmental policy since the coup year in 1961 to the 1979 his assassination year, and the developmental-state policy was extended until 1987 as the year of complete transition to the democracy, as his successor Presidents Jun, Doo Hwan and Rho Tae Woo, who were risen from military elite statues.

By and large, the ‘developmental state’ concept can be reflected through the Chalmers, Johnson’s study of Japan’s economic development. Johnson finds out successful industrial transition of Japan case can be explicated as the centralized government elites’ leading role with development and pretty much free from the sub-social pressures or civil society. Therefore, Japan’s elite leading role during the developmental stage is much similar with Korean case. Which means that, according to C. Johnson, free of elite conflict can be realized to successful transition of economic development that is much different with classical M. Weber’s bureaucratic system theory or the liberal market oriented developmental theory of Lipset’s.

Similarly, M. Woo-Cumings also sees and holds C. Johnson’s study that Japan and Korean case is overlapped with the logic of ‘developmental-state’ model which can be explained and justified as a rationally planned state centric market interferes for economic growth. (Meredith Woo-Cumings: 1999 and Bruce Cumings: 1997) and also can see (Alice Amsden: 1989 “Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization”) Prof. Cumings says “Economic Planning was another wrinkle that Park borrowed either from the Japanese in Manchuria in the 1930s or from the North Koreans thereafter; successive five-year plans unfolded from the hallowed halls of Economic Planning Board (EPB), known as Korea’s MITI, after Japan’s Ministry of Trade and Industry. The First Five-Year Plan was to run from 1963 through 1967, but Americans in the Agency for International Development (AID) mission did not like it, and refused to certify it for foreign lending. It never really got off the ground. The Second Five-Year Plan (1967-71) was more to their liking, but the Koreans had also learned how to muddle American minds.” (Bruce Cumings: 1997. pp. 313-314.)

Comparative application of the President Park’s developmental model case to the Japan’s experience is some what controversial and there are lots of on-going debates in the field of academia because of there exists various study facts of similarities and differences. Firstly, the similar case can be analyzed by focusing on the ‘timing’ in the development. For example, Albert O. Hirschman defined its ‘industrial timing,’ in which the one category is the ‘Late-industrialization’ and the other is the “Late-late industrialization”. According to A. Gerschenkron, Late-industrialization is indicated to the cases of Germany, Italia, Russia, and Japan that are one stage behind to the early industrialized case of developed England. And the ‘late-late industrialization’ is termed to point out the developing Third world, such as Latin American countries.

Clearly, Korea case is categorized into the nominal definition of “late-late industrialization” as much similar with developing Latin America countries when it reflected by the analysis of A. Hirschman’s. Interestingly, it can be argued that actually the Korean case of industrialization is rather much more familiar and close to the category of “late-industrialization” than the late-late industrialization; when one sees the Korean case’s unique preceding mode and its synthesized characteristics of the domestic political system with industrialization.

Consequently, President Park, Chung Hee’s military supported bureaucratic-authorities development mode and procedure is much more similar to Japan’s authoritative regime in 1930s than the experiences of Latin American military regimes. (Choi, Jang Jip: 2002) In addition that looking into the prism of the individual analysis, Korean industrialization was largely directed by an idiosyncratic President Park’s personal ruling idea and his vision on the national political economics. In quotations of Bruce Cumings, it is noted as, “In Park’s first book after the coup, Our Nation’s Path, regime scribes lauded the Meiji Restoration as a great nation-building effort; but it was really the ‘Manchurian model’ of military-backed forced-pace industrialization that Park had in mind.” (B. Cumings: 1997. p. 311.)

Chalmers Johnson also rightly called attention to the Manchurian model of military-backed foced-pace to that “Manchukuo-group” in his seminal MITI and the Japanese Miracle (1982). “Park Chung Hee was a stolid son of Korea’s agrarian soil who, like Kim Il Sung, had come of age in Manchuria in the midst of depression, war, and mind-spinning change. In this radicalized milieu he had witnessed a group of young military officers organize politics, and a group of young Japanese technocrats quickly build many industries-including Kishi Nobusuke, who later became prime minister of Japan.” (Chalmers Johnson: 1982)

However, the study of Korean model, so far, has been analyzed various ways and overproduced its volumes from international and domestic academia by comparative study method; such as, comparative political development study of Korea and Taiwan model v. Syria and Turkey model cases by the U. of Virginia Professor David Waldner’s thesis of “State Building and Late Development”. Professor Waldner employed the “levels of elite conflict” as an basic “unite of independent variable” for the analysis: While Syria and Turkey had high levels of elite conflict existed, relatively Korea and Taiwan had experienced “low levels of elite conflict” that can smoothly transited to the stage of “Developmental-state” in which stage therefore can get enhanced capacity to create “value” and “sustainable development” based on production of low-cost goods that are competitive on world markets with continuous shifts into higher value-added goods. (David Waldner: 1999)

III. Authoritarian Industrialization and Struggle Democracy

In looking back especially the history of modern Korean democracy, the relationship between authoritarian industrialization and democracy was easily seen its critical nature not only Korean themselves but also all foreigners of good-hearted epistemic community can get empathic feeling as disturbing contrast during the Park’s regime. In Korean industrialization case, there are significant contrasting opinions are still remained that regarding “how to interpret” the relationship between industrialization and democracy. The first opinion remarks that though economic growth had been speeded during the Park’s regime, there was lack of genuine sense of democratic political values, including political spaces in democracy. The other states that political democracy was largely sacrificed in order to promote economic growth first to the national policy as inevitability was necessary during the era of Cold War international system. So, the latter point of view again can be deduced into sub-opinionated position that the high level of economic growth output during the Park’s regime can be appreciated as an indomitable developmental leadership and prudent as its well-planned policy machine administrations of the Park regime that preferred cohesive nexus building in capitalism and thus excluding people and labors were allowed oppression in the logic of high level of economic growth first development policy. (Ho Cheol Son 1995: pp. 147-148)

However, two contrasting viewpoints reflect that the driving force of economic growth under the Park’s leadership was composed of three dimensional administrative factors of internal and external context, and ideological conflictions with systemic adjusting reflection on competitive international environment of world capitalism, land reform, the historical and geopolitical conditions of the division in Korean peninsula, at the same time, the strong role of the state and an abundant and diligent labor forces in low wages. The central issue that surrounding the relationship between economic growth and democracy can be reflected by the counter-factual assumption possible; such as, if it were progressed under a genuine democratic political system, then there were situation as hard to promote rapid economic growth. In other words, the question is that it can be justified as an authoritarian political regime is an inevitable and necessary factor for achieve economic growth in the actual processing stage of “take-off” of development. Seeing form the level of fact judgment, which regarding to this issue’s historical modernization experiences looked to be pessimistic. For instance, there were empirical patterns existed in reality where a developing state that faced overcoming efforts against international capital markets’ pressures into the periphery, and at the same time there were assigned for the achieving “take-off” stages to the late industrialization, moreover there were also temptations of inevitable setting up highly centralized state apparatus requirement as sacrificing short term interests through avoiding pressures of redistributions from multitude. Where there are examples of the former Soviet Union and China’s state socialist development, and represented as late capitalist development actors of Japan and Germany are no exceptions to this developmental rule as provided historical evidences (Ho-Ki Kim, 1995). In other words, the extensive regime of accumulation founded on low-wage controlling, and long-hour labor orientations seem to be closed to a “selective affinity” with a coercive and violent and oppressive kind of bourgeoisie state rather than a care and deal with “class-friendly” oriented state. (Ho-Ki Kim, 1995)

Another counter-factual debating study question is possible when it consider under factual and normative tension that the relationship between economic growth and democracy, there is the argument and question in contradiction that whether authoritarianism looked to be more efficient in stimulation economic growth than democracy, so it may be justified that developing state ought to be pursued under the guiding in authoritarianism and therefore democracy could be restrained its degree and durations. Can it be justified; whether economic growth and its capital order and its astute management of stability in a system of capital protocol under the logic of dependency which would be more important than categorical Kantian systemic imperatives ethics of human rights, political freedom and equality of civilian rights? For considering this issue, Professor Ho-Ki Kim suggests that it is reasonable to review past social survey of certain class level as an inferring on the evaluation of history because of it is affected by pervasive of the attitudes at the time which it is interpreted. In 1967, the social survey focused at the level of intellectuals presented interesting results although it was not enough number of survey participants. (Hong Seung-jik, 1967: pp. 161-167. this survey was administered to 761 university professors and 754 news press reporters) The questionnaire was “What would you think is the most important factor or element of modernization when considering the currently given state of affairs in South Korea?”, an large proportional response outcomes as an overwhelming 29.6% of respondents stated “industrialization” and 22.6% stated “improvement of citizens standard of living”, while only 7.1% of respondents stated “the democratization of the political system” and “13.0% stated “the promotion of rationalism and science in daily life”. Interestingly, moreover, the result in which 60% of respondents replied that they would sacrifice personal freedom for the sake of economic development presents almost average intellectuals attitude toward strong hope to modernization support during the underdeveloped era at sixty in South Korea.

As the Korean intellectual’s survey shows that during the 1960s the major issue of industrialization carried an overwhelming importance in popular attitudes. Horrible and devastating memories of the Korean War reflected on strong desire and hope for setting up reestablishing order and stability through persuasions on improving living conditions as overcoming very plight reality of lack of “basic subsistence strategy” as under-nutrition food quality, that related the break agricultural farming circumstances since immediately after the Korean War. Therefore such hopes and basic subsistent material desires naturally provided the mental psychology for support industrialization success although it is planned by demanded authoritarian top-down styled national scaled mobilization. Yet, considering other side of ethical sense about it, it seems to very uneasy to pardon and accept its justification such ruling that largely executed and administered authoritarianism of the Park regime while sacrificing ethos of democracy and regarding on only can appreciate because economic growth was achieved rapidly. Although there had been happened that selective affinity between political authoritarianism and early stage of pre-capitalist industrialization and large number of multitudes desired economic growth, the one-sided and unbalanced justification for authoritarian regimes hard to be given some of positive appreciation.

However, the choice between economic growth and democracy is largely oversimplified various human values and it was many parts regarding on an interpretation of biased historical side that only focused on results without sufficient consideration of its causality and origin by using righteous logos and its processes in ethos. Ultimately, the important considering aspect is how much effort had been done by the Park regime’s investment in combining at the degree of proportional equality of economic efficiency and democratic freedom criteria. For instance, the series of disturbing political reforms such as the regime’s artificial alterations of the Constitution through astute amendment for building permanent political power nexus which enabled Park to run for a third term in violating of Presidential nomination rule and setting up October “Yushin” system which contradicted procedural democracy and the uncomfortable authoritarianism that evidenced the extent of the undemocratic and exclusionary nature of the Park regime.

Such a complex issue needs to be look at forest as if seeing overall big picture rather than some trees. Although the evaluations of industrialization and democracy to be considered empirical problematic area that related experiential problems, yet, it is also innate a theoretical comparative point of dispute. For instance, there is problematic theoretical hypothesis of modernization; according to Lipset, if an economy is developed in certain positive GNP output, then the possibility for the realization of democracy is escalated (Lipset, 1980). Viewing from scaled perspective position, there can see a significant correlation between economic growth and democracy, yet there also exists various contexts and contingency can be found existence of intermediate variables between two relations. For instance, according to Rueschemeyer and Stephens, as capitalist industrialization gradually increasing the scope of density in civil society in which augment of civil society can set up the foundation for political systematization of the governed classes of society, it can also able to transforms the working class into a checking and balancing power as impact upon the authority of the state. (Rueschemeyer, Stephens and Stephens, 1992: They defined civil society as a totality of social institutions and associations, both formal and informal that are not strictly “production-related” nor “governmental” or familiar in character) In such historical analysis through experiences, in the relationship between economic growth and democracy, the major conditions of the growth of civil society and the formation of the working class are important in their roles as can be dealing intermediate variables to the progress and its feedback with their surrounding environments.

IV. The Korean Experience of Civil Society and Democracy

Despite normally there is having a sustainable long term tendency as quoted “viable” democracy in the usage of G. Almond, however, there exists relativity that when democratic path would situated in the short term, there to be faced some possibility for a retrogression within democracy depending on the state’s surrounding conditions. The causality is the direction of democratization is determined by the logic and process of balance of power between power bloc political forces and non-power bloc political forces when the existing governing system is confronted by crisis. Under the Park regime, despite the continuing social movements by non-power bloc political forces such as civil society and the working class, they were not mature enough to rival the power bloc political forces. However, the Korean bourgeoisie did not much embrace democracy and were perceived rather be the most faithful allies to the authoritarian regime (Shin Gwang-yeong, 1995: p. 115). The theory assertion by Barrington Moore Jr. that “without the bourgeoisie, there is no democracy” is not exactly relevant in the case of South Korea. At the same time, the assumption of modernization theory that economic growth contributes to the development of democracy would be reasonably appropriate when only if the growth of civil society were progressed widely and active participations of the working class were conditioned as if an important acting unit of intermediate variables (Jeong Sang-ho, 1966). True, it is a fact that, the potential seeds of viable democracy were cultivated in the internal dynamics of the industrialization promoted by the Park regime during the 1960s and 1970s (Ho-Ki Kim, 1995). Before it could actually sprout through the June Democratization Movement in 1987, such desire for civil society participation democracy had to face harsh suffering by the government of another oppressive authoritarian regime under Chun Doo-hwan who is an almost exact little figurative mimesis of Park, Jung Hee.

V. Conclusion:

Since the era of 1960s to 1980s, the Korean industrialization process is very rapid, and it marked unprecedented world’s historic economy growth record as its annually constant increasing of the volumes of growth. Such rapid developmental state leading industrialization process can affect the political system’s transition. In the year of1972, that political transition was actually happened that change was from a pseudo-democracy system to a polarized authoritative dictatorship system. This study finds that such political system change occurrence is not much actually related with the claims of necessity of ‘deepening’ industrialization. On the contrary, that transition was largely interrelated with the real causalities: the internal causalities are the large governing entity size, and its constant growth of military backed bureaucratic institutions, and especially President Park’s idiosyncratic ambitions on permanently holding Presidential power as his attachment on the dictatorship oriented power nexus web system; an external causality was largely related with the change of the U.S. foreign policy direction to Asia that normalization with China and dialogues with communist regimes during the Nixon era also affected to Park’s leadership. And President Park sees the Nixon doctrine as a wonderful chance to building his own individual political power nexus line and a great chance to free from the United States’ constant support and influences on the value of democratization. In fact, the Nixon doctrine had executed significantly sudden reducing Korea’s developmental finance budget and quantitative material defense security support. Thus, the year of 1972, the Korean political system change that turn reinforcement into the strong bureaucratic-military-authoritative Korean “Yu-sin” system was occurred autonomously within the area of 1) internally already given domestic conditions of the largely expending size of Korean political and military defense institutions in the era, and 2) external circumstance of World affair that the Nixon’ doctrine’s change in foreign policy impact upon North-East Asia, instead of the necessity and awareness of ‘deepening’ economic development.

Bibliography

Adam Przeworski and Ferdinando Limongi. “Modernization: Theories and Facts.” World Politics Vol. 49, No. 2. 1997.

Albert O. Hirschman. “The Political Economy of Import-Substituting Industrialization in Latin America.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 82, No. 1. 1968.

Alice Amsden. “Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization.” New York: Oxford University Press. 1989.

Bruce Cumings. “Korea’s Place in the Sun.” A Modern History. W.W. Norton & Company New York, NY: London. 1997.

Chalmers Johnson. “MITI and the Japanese Miracle.” Stanford: Stanford University Press. 1982.

Choi, Jang Jip. “Democracy after the Democratization.” Humanitas Press. Seoul Korea. 2002. (in Korean)

Lipset, Seymour M. “Political Man.”: The Social Bases of Politics. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.1980.

Meredith Woo-Cumings. “The Develpmental State.” Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1999.

Kang Min and Han, Sang Jin. “Bureaucratic-Authoritarianism in Korea.” Seoul National University Conference on the Dependency Issue in Korean Development. 1983.

Moore, Barrington Jr., “Social Origins of Dictatirship and Democracy.”: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston: Beacon Press. 1966.

O’ Donnell, Guillermo. “Modernization and bureaucratic authoritarianism.” Berkeley: University of California Press. 1973.

Hong, Seung-jik, Intellectuals and Modernization. (1967), Social Researdch Institute of Korea University. (in Korean)

Kim, Ho-Ki. “Modern Capitalism and Korean Society.” Seoul: Sahoebipeyngsa. 1995. (in Korean)

Lee, Jung Bock. “Analyzing & Understanding Korean Politics.” Seoul National University Press. 2006. (in Korean)

Ruschemeyer, Dietrich, Evelyne Stephns and J. Stephens, “Capitalist Development and Democracy.” Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1992.

Shin, Gwang-yeong. “The Concept and Formation of Civil Society.” in Pal-mu Yu and Ho-ki Kim (eds.), Civil Society and Civil Movements Seoul: Hanul. 1995. (in Korean)

Son, Ho-cheol, “50 Years of Korean Politics after Liberation.” Seoul: Saegil. 1995. (in Korean)

Waldner, David. “State building and late development.” Cornell University Press. 1999.

Web:

https://www.scribd.com/document/40604177/Korean-Development-Model-by-Heung-K-Sim